Users Are Not Items: Rethinking E-Commerce User Modeling

“Users are not products.” It sounds obvious. A product is static: a blue cotton shirt, size medium, $49.99. A user is dynamic: “I’m looking for a shirt for a beach wedding, not linen and I’d prefer blue, but maybe show me some other options?”

And yet, the AI models powering modern e-commerce largely ignore this distinction.

In our previous blog posts, we explored how vision-language embedding models like OpenAI’s CLIP map images and text into a shared embedding space. There we dived into the short-comings of this approach in e-commerce domains, specifically its architectural limitations for interleaved product understanding. This paradigm was transformative for item representation, enabling semantic search and solving old cold-start problems. However, it also established a “symmetry assumption”: that the model should treat text and images as interchangeable entities in that shared space.**

This post argues that this assumption is the single biggest bottleneck in e-commerce discovery. We will focus on the deep-seated difficulties of the ‘shared-embedding approach’ for user modeling, identifying the fundamental gaps between what these models provide and what truly personalized e-commerce requires.

The User Modeling Gap

Our previous blogs have focused primarily on representing items. It focused on how we encode products, their images and their attributes to enable better retrieval. E-commerce, however, is not just about items, it is also about users. Although the research community has made significant progress on item representations, the user side of the equation has received far less attention.

The standard approach treats users as simply “the other side” of the retrieval equation. You embed the queries of the user with the same model as for the item, compute similarity and return results. This symmetric paradigm inherits directly from visual language modelling, which treats text and images as interchangeable entities in a shared embedding space. But users are not just items with different inputs. They have fundamentally different properties that vision-language models were not designed to capture.

This gap is not just a theoretical concern. It affects core business outcomes. It affects how well we handle new users (cold start), how effectively we personalize (preference modeling), how naturally users can express complex intents (query composition) and ultimately, how efficiently shoppers discover products they will purchase. Understanding this gap is essential for building discovery systems that match how people actually shop, not just how models were trained to match images and text.

What Is Currently Out There

Since the release of OpenAI’s CLIP (Radford et al., 2021), several open-source alternatives have extended this paradigm. SigLIP (Zhai et al., 2023) replaced softmax with a sigmoid loss to improve efficiency and stability; Jina CLIP v2 (Koukounas et al., 2024) introduced multilingual and multimodal improvements; Nomic Embed (Nussbaum et al., 2024) emphasized reproducibility and long-context embeddings. Libraries such as Marqo have further adapted these representations for e-commerce retrieval. The standard approach remains largely the same. While the paradigm has been transformative for item retrieval, it inherently limits user modeling. It assumes that the embedding space is sufficient to represent intent, not just content.

Most existing user modeling strategies built on top of CLIP or similar dual encoders inherit this symmetric assumption. The simplest approach treats each user query as an independent text embedding, assuming no persistent user state. Slightly richer variants aggregate clicked or viewed item embeddings, averaging them to form a “user vector.” More sophisticated approaches use sequential encoders (RNNs or Transformers) to model temporal dependencies across a user’s interaction history (Hidasi et al., 2016). Yet, these methods still conceptualize user modeling as an afterthought to item representation. The models remain trained to represent items and captions, not to understand the latent goals driving a user’s search behavior. Consequently, they struggle with personalization, cold-start situations and compositional intent (e.g., “something like this, but more festive”).

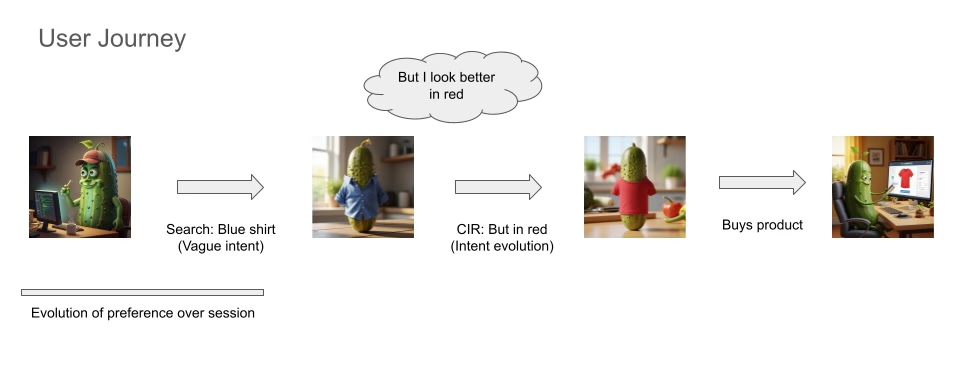

Composed Image Retrieval provides an illuminating parallel. In CIR, a model must retrieve a target image based on a source image plus textual modification (e.g., “this jacket but in leather”). Works like Chen et al. (2020), Baldrati et al. (2022), and Saito et al. (2023) explore different architectures to improve compositional reasoning. CIR highlights a fundamental limitation of standard dual encoders: they struggle to represent relational transformations between concepts. This challenge mirrors user intent modeling in e-commerce, where a shopper’s evolving query is rarely a static point but a transformation from past preferences. Examples of this are “I liked that shoe, but in a different color” or “show me this style but for summer”. CIR research therefore serves as a testbed for reasoning about how embeddings can change meaningfully. This is a core need for modeling dynamic user intent.

Traditional recommender systems have long used collaborative filtering (CF) (Koren, 2009) to learn latent user–item interactions from historical data. However, CF suffers from the cold-start problem (Schein et al., 2002; Gope & Jain, 2017). Content-based and hybrid systems mitigate this by incorporating product metadata, images and attributes (He & McAuley, 2016). Vision-language models offer an appealing alternative: zero-shot recommendation based on semantic similarity, without needing explicit interactions. Research such as Hou et al. (2023) and Wei et al. (2023) has attempted to adapt contrastive or graph-based methods for this purpose. Yet, in most cases, user modeling remains reduced to interaction aggregation rather than intent understanding. These models know what a user interacted with, not why.

Despite this progress, current multimodal retrieval systems fail to capture several key dimensions of user behavior:

Temporal Dynamics: User preferences evolve over time. It evolves both within sessions, across seasons and through context changes. Time-aware recommender systems (Campos et al., 2014) and sequence models (Covington et al., 2016) highlight the importance of temporal signals, yet vision-language models still treat each query as temporally isolated.

Uncertainty and Exploration: Users often enter exploratory search modes (White & Roth, 2009), expressing vague or evolving needs. Embedding models that output single deterministic vectors fail to capture uncertainty or ambiguity in intent.

These limitations underscore the need for asymmetric architectures that explicitly distinguish between users and items, treating user representations as goal-oriented processes rather than static embeddings.

Bridging the Gap

The future of user modeling in multimodal e-commerce lies not in building large CLIP variants, but in rethinking the underlying paradigm. User and item representations should be treated as asymmetric entities. Users are dynamic, uncertain and compositional agents. Items, on the other hand, are structured, multimodal objects. Bridging these representations will require temporal modeling, structured retrieval and e-commerce-native training data that reflects how people actually shop. It shifts the focus from web-scraped image-caption pairs to real user sessions, interaction patterns and the modalities that matter in ecommerce. Only then can recommendation systems move from matching semantics to modeling intent. This is the true driver of discovery.

References

- Radford, A., Kim, J. W., Hallacy, C., et al. (2021). Learning Transferable Visual Models From Natural Language Supervision. International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML).

- Zhai, X., Mustafa, B., Kolesnikov, A., et al. (2023). SigLIP: Sigmoid Loss for Language Image Pre-Training. arXiv preprint arXiv:2303.15343.

- Koukounas, D., et al. (2024). Jina CLIP v2: Multilingual Multimodal Embeddings for Text and Images. arXiv preprint.

- Nussbaum, Z., et al. (2024). Nomic Embed: Training a Reproducible Long Context Text Embedder. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01613.

- Chen, Y. C., et al. (2020). Compositional Learning of Image-Text Query for Image Retrieval. Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV).

- Baldrati, A., Bertini, M., Uricchio, T., & Del Bimbo, A. (2022). Conditioned and Composed Image Retrieval Combining and Partially Fine-Tuning CLIP-Based Features. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.07706.

- Saito, K., et al. (2023). Pic2Word: Mapping Pictures to Words for Zero-shot Composed Image Retrieval. Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR).

- Covington, P., Adams, J., & Sargin, E. (2016). Deep Neural Networks for YouTube Recommendations. ACM Conference on Recommender Systems (RecSys).

- Hidasi, B., Karatzoglou, A., Baltrunas, L., & Tikk, D. (2016). Session-based Recommendations with Recurrent Neural Networks. International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR).

- Hou, Y., He, Z., McAuley, J., & Zhao, W. X. (2023). Learning Vector-Quantized Item Representation for Transferable Sequential Recommenders. The Web Conference (WWW).

- Wei, W., Huang, C., Xia, L., Xu, Y., Zhao, J., & Yin, D. (2023). Contrastive Learning for Representation Degeneration Problem in Sequential Recommendation. WSDM.

- White, R. W., & Roth, R. A. (2009). Exploratory Search: Beyond the Query-Response Paradigm. Synthesis Lectures on Information Concepts, Retrieval, and Services.

- Campos, P. G., Díez, F., & Cantador, I. (2014). Time-aware Recommender Systems: A Comprehensive Survey and Analysis of Existing Evaluation Protocols. User Modeling and User-Adapted Interaction, 24(1-2), 67-119.

- Koren, Y. (2009). Collaborative Filtering with Temporal Dynamics. ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining.

- Schein, A. I., Popescul, A., Ungar, L. H., & Pennock, D. M. (2002). Methods and Metrics for Cold-Start Recommendations. ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval.

- Gope, J., & Jain, S. K. (2017). A Survey on Solving Cold Start Problem in Recommender Systems. International Conference on Computing, Communication and Automation (ICCCA).

- He, R., & McAuley, J. (2016). VBPR: Visual Bayesian Personalized Ranking from Implicit Feedback. AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence.